[ad_1]

College students are far more willing to talk to their friends about unwanted sexual experiences than they are to campus police, a crisis center or a university employee, according to a new, large-scale survey by Vector Solutions, the nation’s largest provider of sexual violence risk-management training materials for universities.

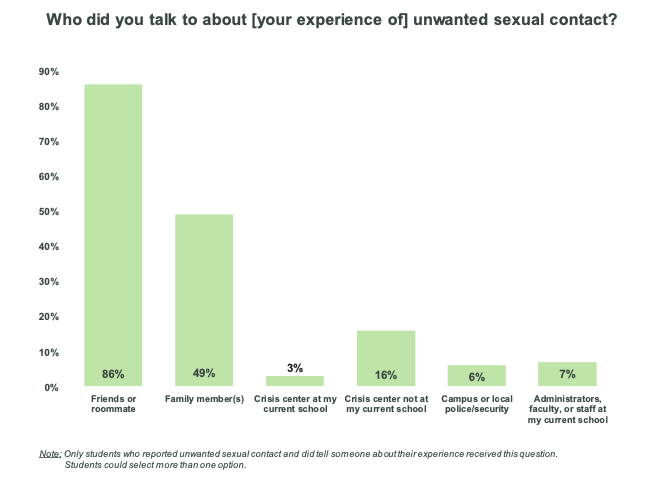

Of the 14 percent of respondents who said they had experienced unwanted sexual contact, 86 percent told friends or roommates, and about half told their families. But only 6 percent told campus or local police, 7 percent told a university employee, 3 percent went to an on-campus crisis center and 16 percent went to an off-campus crisis center.

Experts say the report aligns with existing research on campus sexual assault victims.

“Mostly, this is consistent with what many other surveys find in terms of rates of sexual violence, rates of disclosure, reasons for disclosing or not disclosing,” said Carrie Moylan, a professor at Michigan State University who specializes in gender-based violence.

A graph showing who students turned to after a sexual assault.

The Campus Prevention Network National Insights Report draws on responses to a precourse survey taken by students who completed Vector’s Sexual Assault Prevention for Undergraduates training, which students are often required to take before their first year of college. It includes responses collected over eight months from more than 458,000 students at 383 U.S. colleges and universities.

Vector Solutions has long collected data for this survey and other surveys associated with its educational materials, sending each institution that utilizes its courses a report of its students’ responses to help officials better understand the climate surrounding sexual violence on their campus. Vector has also historically sent data to researchers upon request. But this is the first time it has publicly released its findings; Holly Rider-Milkovich, vice president of education strategy, said she hopes the data will help both institutions and the general public gain a wider understanding of undergraduates’ attitudes toward sexual violence on campus.

“We have the most robust database on health, safety [and] well-being issues in higher education, probably in the entire globe,” she said. “The exciting thing is that we’re committed to doing this going forward, and so hopefully our higher education community is going to come to not only use the data that they receive from their own impact reports … [but] then be able to benchmark” that data against the national insights report.

Levels of Intervention and Support

According to the survey responses, students feel confident in their ability to intervene if they believe someone is in an unwanted sexual situation; 77 percent reported that they would step in. They also expressed high levels of support for both bystanders and survivors; 95 percent of respondents said that they would respect another person who stepped in to prevent sexual violence, and 82 percent said that they don’t place blame on someone who was assaulted while intoxicated.

“I think there’s been a lot more social conversation around the role of bystanders, and I think for young people in particular they’ve been hearing about these concepts in terms of bullying and other forms of violence they might be exposed to even as high schoolers, so it doesn’t surprise me to see that students feel confident in those skills,” said Moylan. She noted, however, that students’ predictions about how they will fare in such situations don’t always align with how they act in real life.

Students answered a follow-up survey between 30 and 45 days after taking the Vector Solutions course, which asked them to outline how they responded in a number of actual situations. Of those who reported that someone had told them about a sexual assault, 94 percent of women and 91 percent of men said they helped that friend access resources.

In the same follow-up survey, 87 percent of students said that in a hypothetical situation where they feared someone was at risk of sexual assault, they would step in to ask the victim if they needed help; 74 percent said they would check in with that person later. Fewer—62 percent—said they would separate the two individuals, and fewer than half said they would confront the assailant.

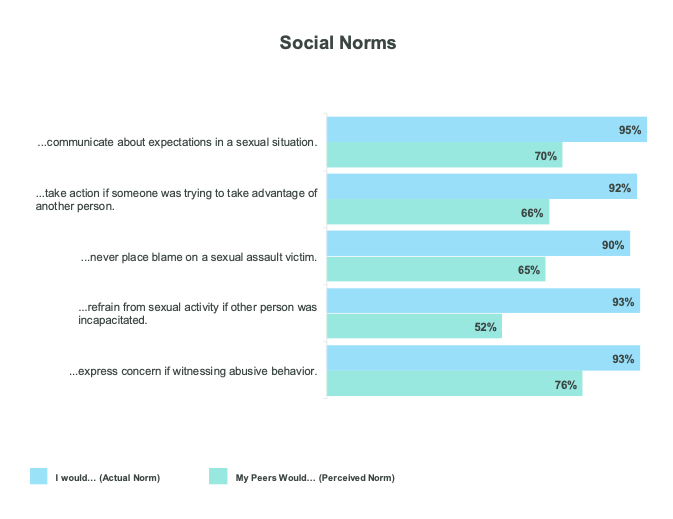

A graph showing the difference between what students believe about their peers attitudes and behaviors towards sex and sexual violence, versus what they say they actually feel.

But the report also revealed a gap between how much students trust themselves compared to their peers in practicing “positive behaviors” regarding sex and sexual violence. While 93 percent of students said in the original precourse survey that they would refrain from having sex with a partner who is incapacitated, only 52 percent believed their peers would do the same. And while 92 percent said they would intervene if they saw someone “trying to take advantage of someone else sexually,” only 66 percent believed their peers would.

Report Draws Criticism

Tracey Vitchers, executive director of the campus sexual assault education nonprofit It’s On Us, expressed concern that the survey’s respondents only represent students at schools that contract with Vector Solutions to provide their campus’s sexual violence risk-management trainings.

“This data is coming from schools that are contracting with them and are able to pay to have this service, and I don’t know what Vector Solutions charges, but I assume it’s not particularly cheap,” she said. “So, these students, before they get into the actual risk management program that they offer, may not be reflective of the actual student population that is enrolled in college today.”

She also said that her organization’s research has found that students often respond to surveys during online sexual violence trainings with answers they know their institution is looking for, rather than disclosing how they really feel.

Rider-Milkovich said she did not have data to specifically back up the idea that students were answering sincerely; however, due to the high number of respondents, “we can really have tremendous confidence in the value of the data and the value of the insights.”

Vitchers also critiqued the data for being presented in what she viewed as a “a sales and marketing document.”

“It becomes a question of ethics as to why they are collecting this data, to what end are they collecting the data and what are they doing with it,” she said. “Is it leading to changes in their prevention education programming?”

Rider-Milkovich said in an email that a “clear external sign of the strength of our data” is that scholars at prominent research institutions such as Duke University have utilized to secure funding for their peer-reviewed research. She also noted that the survey results have led to improvements in the company’s course offerings, including changes to language in its alcohol risk management training, Alcohol EDU.

“We are committed to informing and improving prevention practices across the nation,” she wrote. “Our team is deeply driven by—and impacted by—this work each day. Many of the questions in our surveys are not at all related to the content of our courses and are included to provide administrators with insights to support their prevention strategy.”

[ad_2]

Source link